During the Forecasting Healthy Futures Global Summit 2025, FHF presented its 2025 FHF Resilient Futures Award to Matea Cañizares, a 17-year-old high school student, and Dr. Daniel Romero-Alvarez, an infectious disease eco-epidemiologist working as an associate professor at Universidad Internacional SEK, for their project, “Heat Stress Factors in Ecuadorian Schools: A Multi-case Study of Environmental Conditions in Three Ecoregions." While FHF received a strong pool of submissions in response to this year’s open call for abstracts and posters, their project stood out for its scientific rigor, originality, and its high potential to impact climate-resilient public health. The selection committee also recognized their project for its clear commitment to equity and community relevance, especially in applying satellite data to highlight an often-overlooked issue: the health risks posed by extreme heat in educational environments.

Congratulations on being named this year's FHF Resilient Futures Award winners! Can you tell us about your project and how it came about?

CAÑIZARES: So, I play football (soccer) almost every day here in Ecuador, but since Ecuador is close the equator, we’re constantly dealing with excessive temperatures. And since I’m often playing on fields, I’ve realized these environmental factors are affecting my well-being and can inhibit my physical activity. So, I decided to learn more about this.

In Ecuador, school infrastructure lacks standards on temperature control, solar protection, or vegetation cover. So, this study looked at various environmental conditions in schools across Ecuador's ecoregions using satellite data – and how heat stress and radiation levels are impacting our health.

Dr. Daniel Romero-Alvarez, my mentor, taught me how to use Google Earth Engine to extract data, and together we studied the impacts of heat on Ecuadorian schools by extracting data on environmental factors in different schools of Quito.

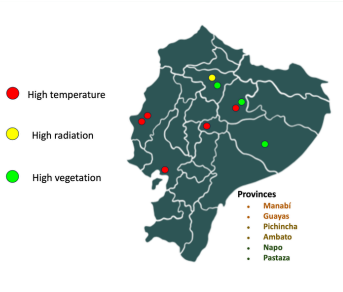

Through the project, we analyzed vegetation, temperature and radiation by looking at vegetation density, temperature levels, and solar radiation in Ecuadorian schools across three ecoregions using space-based technologies with a focus on nature-based solutions to protect human health. We used Google Maps and Google Earth Pro to assess conditions in 3 schools per ecoregion (Coast, Andes, Amazon). We looked at satellite data products and measured land surface temperature, enhanced vegetation index, and downward shortwave radiation.

We found that coastal schools had the highest temperatures and lowest vegetation, Andean schools experienced the highest solar radiation due to elevation, and Amazonian schools had the highest vegetation levels. Only one school had an average temperature below the heat stress threshold (26 Celsius degrees). So, we found an apparent relationship between vegetation and lower temperatures, although the effects varied by region.

We delineated school perimeters as polygons, and the corresponding environmental data were obtained from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) aboard the Terra and Aqua satellites. We were looking at key indicators such as land surface temperature (LST) as a proxy for heat exposure, enhanced vegetation index (EVI) for greenness, and downward shortwave radiation (DSR) for solar exposure.

Our findings show most schools exceed the heat stress threshold on average; however, there is environmental heterogeneity across and within ecoregions. Schools in the Coast region had the highest temperatures, which correlates to strong heat stress whereas schools in the Andes region had the highest solar radiation levels. Lower vegetation index values correlated with increased heat stress across all regions. Only one school had an average temperature below the heat stress threshold. These environmental conditions have critical implications for student health since excessive heat exposure has negative health impacts, while vegetation cover may decrease temperature levels.

Ecuador lacks standards for temperature control, solar radiation protection, and green spaces in schools so our findings also underscore the need for context-specific and climate-responsive educational standards that integrate nature-based solutions for extreme heat mitigation and protection from solar radiation.

I then met with the Ministry of Education to present recommendations since there are no specific policies about how schools should adapt their infrastructures with vegetation and other climate health requirements that impact student well-being. Our research made an impact and that’s made me really happy because this now not just about identifying a problem but also showing a solution.

ROMERO-ALVAREZ: The most amazing thing about this project was being able to use open access data to derive conclusions that can have an actual impact. Basically, we were able to use satellite imagery to obtain data which now benefits not only those in Ecuador but a lot of other countries. Typically, just sharing data is often a challenge, so this project has been not only fascinating but exciting!

CAÑIZARES: Another thing that is very important about our method in using Google Earth Engine is that it's easy to replicate. So other young people who have a basic computer set up with an internet connection can replicate this method, because it doesn't require a lot of skills. Using the code provided in our study, they can study their own environmental factors using the same satellite technology and better understand data from their own local context and their own schools to realize the impact that radiation has on vegetation, temperature, and their well-being. I’m excited because this has the potential to work on a global scale. So, I hope other young people can learn from this and then use data satellite to help influence public policy and create even more of an impact. This study can be replicated using a representative sample to produce national standards for Ecuador or in other countries to identify the environmental conditions of schools with the aim of assessing their needs.

ROMERO-ALVAREZ: For me, one of the most interesting consequences of this project is precisely how we can use open data streams to convey messages. We hope that this study can help inspire others. For example, if someone in Peru wanted to assess whether environmental variables affect the health on their school students, they can easily take our data or go with what we discovered. Because this study is replicable, it’s something that can be implemented everywhere so that something that makes us very happy.

Your project was recognized for its inclusion of equity and community relevance. Why was this important to include?

CAÑIZARES: Yes, that was another thing. While our study didn’t focus on distinguishing between public schools and private schools, our study did find that private schools had higher levels of vegetation, due to increased resources to implement landscaping, whereas public schools, in the same region and similar locations, didn’t have the resources to focus on vegetation, resulting in higher temperatures. Our hope with our studies is to further assess how these differences impact student well-being and perhaps use satellite data to impact public policies, such as perhaps giving more money to public schools to increase vegetation or help reduce temperatures to improve the well-being of students.

ROMERO-ALVAREZ: Equity is fundamental because the essence of problem-solving is to be open to different perspectives and different views. Sometimes we forget to hear local voices, because we are super concentrated, for example, in academia or science-based theories, when in fact, a lot of times, the local population, the people that are actually experiencing the problem or the situation have a lot of wisdom that we should definitely consider in order to propose a solution or something. These sorts of open data streams are proving resources so we can actively help communities to be more aware of what is happening in their surroundings and to take local action.

You also addressed nature-based solutions for health and climate resilience. Can you tell us what you learned?

CAÑIZARES: Nature-based solutions, or NbS, are considered a valuable educational tool, particularly for promoting outdoor learning in schools. However, the relevance of vegetation in schools for planetary health and climate resilience remains less apparent to policy- and decision-makers. Studies suggest that the presence of vegetation has an influence on mental health and learning outcomes and that green cover can moderate temperatures. In addition, natural shade can further protect students against solar radiation. Therefore, school greening should be considered an important priority in nature-based actions targeting health risks through improved climate resilience. Investment is needed to first identify cost-effective ways to evaluate and monitor conditions at schools, for example, using digital tools. Second, assess the levels of exposure to moderate and high heat stress and solar radiation levels at schools in relation to vegetation density and characteristics. Third, create or reform school infrastructure standards and provide resources to use NbS to increase or modify vegetation at schools. Fourth, they need to assess the learning outcomes of students before and after interventions. Promoting planetary health must recognize the importance of the school as a critical setting for health and a space for urban greening, especially since children and adolescents spend much of their daytime there. My study on health-related environmental conditions in different ecoregions of Ecuador has garnered the interest of the Ministry of Education and other stakeholders, and may serve as a model for using satellite data to inform and develop strategies for implementing NbS in schools in countries facing similar environmental challenges.

Given the name of the award, ‘Resilient Futures’, what does that mean to you and what’s your hope for the future?

ROMERO-ALVAREZ: Today, all around us, we are seeing the damage that we as humans are doing to the planet. In a way, the planet is throwing these back to us: emerging zoonotic diseases, climate change, landscape alteration, and antibiotic resistance, are examples. A resilient future would be to think about how to survive. Our hope is that science will advise decision makers and policymakers to improve societies as we face all these threats, and a resilient future is precisely trying to use that collective knowledge to confront all these problematic scenarios.

CAÑIZARES: What ‘resilient futures’ means to me is working with children and young people who will become future policy makers. My hope is to help them develop their civic skills and help them analyze and propose solutions using information for decision making and thinking about their life experience. So, this connects with me playing football, which is my lived experience, which motivated me to use information for decision making. I hope that other young people playing football or doing other activities will use their lived experience to propose solutions or to be motivated to identify what digital platforms are available and how they can, in turn, impact policymaking.

Matea Cañizares is a student at Colegio Johannes Kepler, Quito, Ecuador. Dr. Daniel Romero-Alvarez is Associate Professor at the Emerging and Neglected Diseases, Ecoepidemiology and Biodiversity Research Group, Undergraduate Program in Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, Universidad Internacional SEK, Quito,Ecuador.